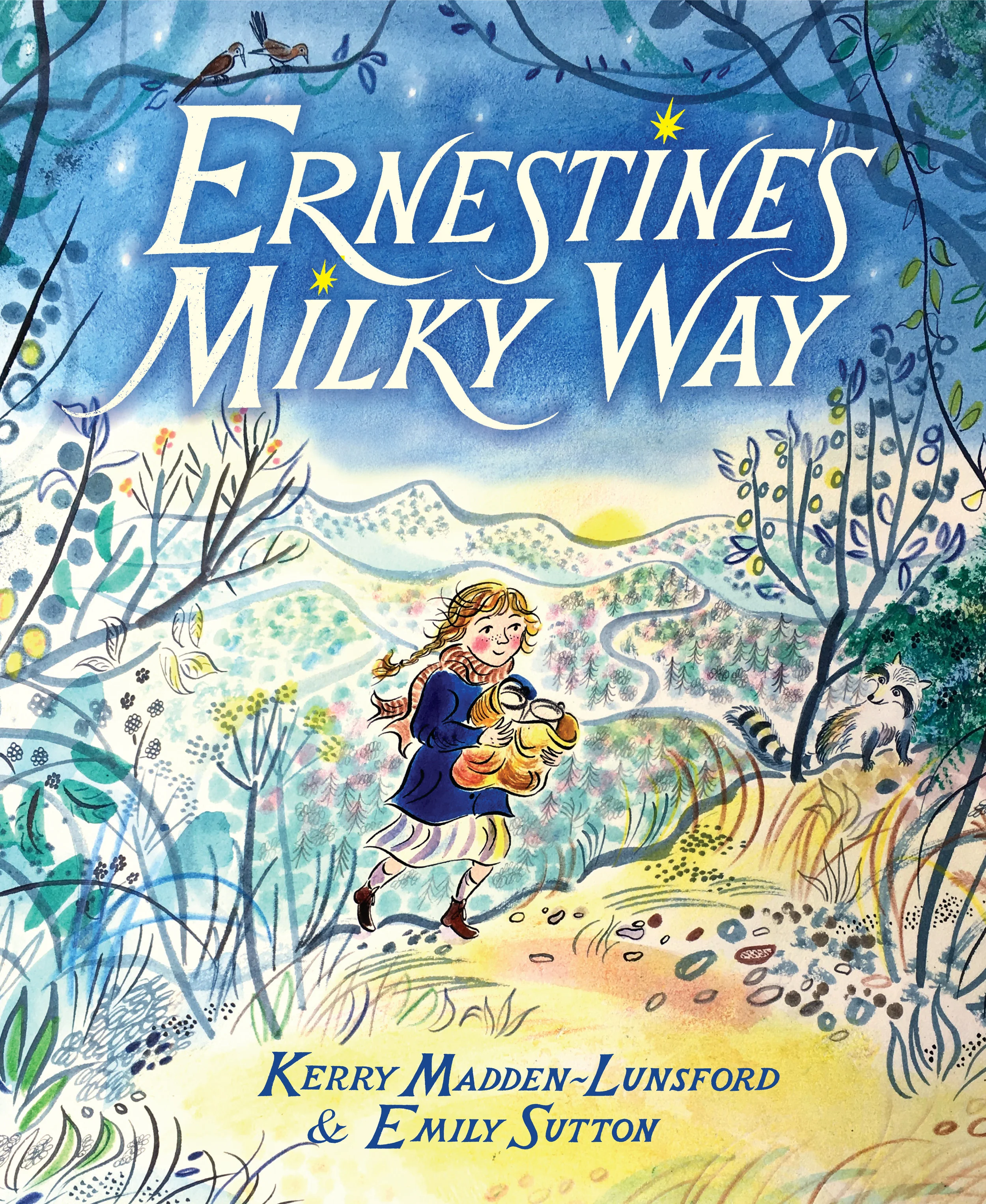

Meet Kerry Madden-Lunsford, and read an excerpt from her new children’s book, “Ernestine’s Milky Way”

Interviewed by Marlena Trafas

“Then I saw the mountains. And I began to get used to seeing the mountains come into view, and they offered me comfort — this lonely teenage girl who’d lived in eight states, mostly the flat Midwest.”

excerpt from Ernestine’s milky way

One day, Mama said, “Ernestine, I need you to do a job for me. Mrs. Mattie Ramsey, who rents the shanty house down yonder, needs milk for her children’s breakfast. Their daddy’s gone off to war too.”

“You want me to carry Ole Peg’s milk all the way to the Ramsey’s?”

“I’d do it myself, darlin’, but Dr. Fairchild says I’ve got to stick close to home with these babies coming.”

Ernestine jumped on top of the milk pail and stuck her chest out. “I can do it, Mama.”

“It won’t be easy,” Mama warned. “You’ll have to walk through the thickets of crabapple and blackberry by the creek, down the path of prickly gooseberry and honeysuckle, past the vines of climbing bittersweet, into the valley of doghobble and devil’s walking stick, and through the barbed-wire fence.”

“I can do it, Mama,” Ernestine repeated. She climbed down off the milk pail and whispered, “I’m five years old and a big girl.”

But did Ernestine tremble a little when she spoke the words?

Editor’s note

Kerry Madden-Lunsford is the author eight books. Her newest picture book is Ernestine’s Milky Way, (Schwartz & Wade/Penguin Random House). She wrote The Smoky Mountain Trilogy for children, which includes Gentle’s Holler, Louisiana’s Song and Jessie’s Mountain, (Viking/Penguin) Her first novel, Offsides, (William Morrow) was a New York Public Library Pick for the Teen Age. Her book, Up Close Harper Lee, (Viking/Penguin) made Booklist’s Ten Top Biographies of 2009 for Youth. Her first picture book, Nothing Fancy About Kathryn and Charlie, (Mockingbird Publishers) was illustrated by her daughter, Lucy Lunsford. Kerry is a regular contributor to the LA Times OpEd Page. She directs the Creative Writing Program at UAB and teaches in the Antioch MFA Program in Los Angeles. The mother of three adult children, she divides her time between Birmingham and Los Angeles. Visit her at www.kerrymadden.com.

The interview below discusses Madden-Lunsford’s most recent book, Ernestine’s Milky Way. The story is based upon the childhood of Madden’s dear friend, Ernestine Edwards Upchurch (1973–2017) who grew up in Maggie Valley, North Carolina.

What drew you to writing children’s books? How do you approach writing for children as opposed to writing for peers?

With my first novel out of print, a new baby (third child), and a dying grandmother, I was furiously writing anything that might sell to make a living — ghostwriting, health articles, a shadow script of a soap opera. I was anxious and sad, feeling like a great fraud. Then 9/11 happened, the ghostwriting gig blew up in small claims court, and I was given something called the gift of desperation. I realized I had three beautiful kids and my husband, Kiffen, an elementary school teacher, was one of 13 children.

Our older two kids had started bringing home children’s novels from school, saying, “Mom, you have to read this.” These titles included: When I was Young in the Mountains, The Phantom Tollbooth, The Giver, Dovey Coe, Catherine Called Birdy, and many others. I had always read adult literary fiction but pausing to read these children’s novels made me remember what it was like to fall in love with a story again. And I wondered if I could do that — write for kids instead of trying to breathe life into depressing drafts of my adult novels that I was working on at the time.

I began to write my first children’s novel, Gentle’s Holler, set in the Smoky Mountains. I was still doing articles about health and had taken on another ghostwriting gig, but whenever I was writing paid gigs for the adult market, my brain felt taxed and stressed. But when I began to write the story of the Weems family in the Smoky Mountains, I felt like I was breathing in fields of wild flowers. I didn’t know if Gentle’s Holler would sell. I only knew I wanted to write about a family living in Maggie Valley, North Carolina and the seeds of this family were inspired by my husband’s stories growing up one of 13 children, the son of a fiddle player in a house full of books and art and music.

The Smoky Mountains in Maggie Valley, North Carolina are obviously a big inspiration to you. Can you speak to the first time you visited the area and when you knew you’d found someplace special?

My father was a college football coach, so I first saw the mountains when I was fifteen. We moved to Knoxville, Tennessee so he could become the defensive coordinator and assistant head coach for the Tennessee Volunteers. I didn’t want to move to Tennessee. I loved Pittsburgh and my all-girls’ school and the field hockey team. In the South at that time, girls were still playing half-court basketball to “protect their ovaries,” so I hated everything about backwater Knoxville, and I grumped about in my room writing letters to friends in Pittsburgh, sending them packets of grits to show them how awful my life was. HA!

Then I saw the mountains. And I began to get used to seeing the mountains come into view, and they offered me comfort — this lonely teenage girl who’d lived in eight states, mostly the flat Midwest. So, I began to feel a spark of joy whenever the mountains first appeared as we drove toward them away from Knoxville. Maybe I began to claim them in a way I’d never claimed a landscape before. In the mountains, I could breathe a little easier, and I was proud of them.

Finding Maggie Valley, North Carolina was an accident. Our daughter, Lucy, was three and our son, Flannery, was five. Norah wasn’t born yet. We were on a family vacation in North Carolina, visiting relatives, and I had the bright idea of taking the kids to Thomas Wolfe’s childhood house. Lucy, pitched a fit on the front porch, screaming hysterically. Who could blame her? Her temper tantrum and my husband trying to console her meant we had to do something different.

The next morning we had to get in the car and drive to Nashville, and I was dreading another car trip. (We still had to drive all the way back to California.) I said to Kiffen, “Let’s take the back roads. Let’s find a map and go the slow way to Nashville and let the kids get out and play along the way.” Kiffen agreed, and so we looked at a map and saw the name of this town called Maggie Valley. I thought it sounded beautiful. Maggie Valley. I suddenly had to see it. Who was Maggie? Did she ever live in the valley once upon a time? I thought it was such a pretty name for a town.

So, we drove to Maggie Valley on the back roads from Asheville, and we went to Joey’s Pancake House and had a feast. We stopped being grownups that day, and we let the kids lead the way. And it was the best. I am just realizing, writing this, how perfect that day was — because we stopped trying to control everything in order to get to Nashville faster.

I never forgot the name of the town, and so eight or so years later, I decided to set my first children’s novel, Gentle’s Holler, in Maggie Valley, the name of that pretty town in the mountains we’d visited with the kids so long ago.

Your friend, Ernestine, whose childhood story is the basis of this book, also played a huge role in your experience of Maggie Valley. How did person and place/character and setting play off one another as you were thinking about Ernestine’s story and writing it into a children’s book?

When Gentle’s Holler came out in 2005, thirteen years ago, Ernestine Edwards Upchurch contacted my PR friend, Rahni Sadler, who was helping me with all the PR in the mountains. So, we sent Gentle’s Holler to Ernestine and she and I began to correspond. I did a big signing at Joey’s Pancake House, the gathering place in Maggie Valley, and then I met Ernestine a few months later on another trip to the mountains, and we met, of course, at Joey’s Pancake House where we had this instant connection. I was worried that Ernestine wouldn’t like me — a California woman from Tennessee who had not grown up in Maggie Valley and was writing about her mountains. But she was so hilarious and we did not stop laughing from the very beginning. I remember thinking — oh we are going to be friends.

Then my publisher, Viking, bought two more Maggie Valley novels, that I had not written yet, and so I needed to spend more time in Maggie Valley. I had not really ever spent any real time there other than when we took the kids when they were little. And Ernestine said, “If you’re going to write about our mountains, your California family needs to learn to spare you.” She also let me write in her cabin up on Johnson Gap one summer, and I stayed with her every time I came to town to do school visits. She became my mountain mother. I can’t even describe how much I loved her. She was just so grounded and funny and real. And she loved books and kids and stories and the mountains — she often said, “I bloomed where I was planted.”

One time, when I was encouraging her to write, I gave her a writing prompt, which was “Describe your first job.” So she told me about carrying a mason jar of milk through the mountains at the age of five. We were in her living room, and I could see little Ernestine carrying that milk and not wanting to drop it or disappoint her mama. I took a walk the next morning before the sun was up, and I thought, Ernestine did this when she was five — crossing a road and barbed wire fence — and I saw the stars in the sky, the Milky Way and I thought, wow, Ernestine carrying milk through the mountains is like her own milky way and the stars would light her way. So it was a seed planted in 2011, and it was a story that would not let me go. I kept thinking I needed to write that story. Finally, I did. I wrote probably 100 drafts before it took shape.

Family and community are big themes in the book. As a writer who has split their time between Los Angeles, Alabama, and Maggie Valley how have these three different places shaped your portrayals of neighborly-ness?

I would have to add another too. I’ve been to Monroeville, Alabama so many times working on the story of Nelle Harper Lee that I feel like I’ve lived there too, and the people are wonderful.

I think having grown up as a football coach’s daughter and lived in thirteen states and abroad (England and China), I have always been seeking home and what it means to be home and to come home.

I was always envious of kids who had grown up together and known each other all of their lives. I was always the new kid, picking up the accent, watching the “mystery and manners” (as Flannery O’Connor wrote) of each new football town. How could I belong? Who would be my friend? Why was I so tall? Why did I look like a boy for so many years growing up? I am now grateful for moving, because it made me seek out the curious people — the people who welcomed me to each place, children and adults. And I always found them, and we connected. Then I would have to say good-bye because we’d move again. My father would say, “You won’t remember these folks! Get in the car, Aunt Gertrude! (his nickname for me when I was being mopey). We got football games to win.” But I vowed to remember my friends, and I’m in touch with many of them still today.

In Los Angeles, we raised our kids there, and Silver Lake and Echo Park and Los Feliz became our home and many parents of our children’s friends became our friends too. We all connected at different stages and ages of our kids, but I didn’t know Los Angeles was home until I had to leave it. And I didn’t know that Alabama was going to stretch into a decade of living away from my husband, but I have found home and beautiful friends here too.

As for Maggie Valley and Monroeville, I did so many interviews and met so many people in each place. I would think of Ernestine growing up in Maggie Valley. I would think the Weems kids and where they might have lived — Fie Top Road, why not? I wandered around “Ghost Town in the Sky” one time when it was empty and being on top of Buck Mountain at an abandoned amusement park gave me such an eerie feeling of wistfulness and longing. I felt like I’d found a kind of home, and I tried to be neighborly when I was interviewing or talking to people — because “I don’t know what I don’t know” — and I wanted to learn from those who did know.

What role has nature, Maggie Valley specifically, played in your own mindfulness?

With Ernestine’s Milky Way, I looked up plants of the Smokies. I did this with Gentle’s Holler too. There are such wonderful names — Devil’s Walking Stick, Doghobble, Jack-in-the-Pulpit, touch-me-nots or as they are sometimes called, “pretty-by-nights.” My husband always planted summer and winter gardens in Los Angeles, and he knew the names of everything. I did not have gardens growing up when I was a kid. It was frozen processed food and canned food and hamburger helper and iceberg lettuce and crockpot meals. Mom would buy “five loaves of bread for a dollar at Winn Dixie” and it was awful bread — the kind that fell apart when you spread peanut butter on it.

But I loved the fresh vegetables and flowers that grew in our Silver Lake garden. We could send the kids down to cut spices for supper or pick carrots or beets. I found I began to need the garden and being outside. My husband made King Kong topiary out of jasmine that loomed over the picnic table in the backyard.

And so, the nature of Maggie Valley was like a giant garden, and I loved walking the mountain paths around Maggie and showing Norah everything. Flannery and Lucy were in high school and college by the time I was writing the Maggie Valley/Smoky Mountain books, so they didn’t make all the trips that Norah made. Norah and I stayed two weeks in Ernestine’s cabin on Johnson Gap. I had to pour gasoline in the generator way up on a dark path where I was warned about a panther. Norah hid under the quilts and said, “If you don’t come back, I’ll just call Ernestine.” She wasn’t worried, but she wasn’t about to go with me to the generator and meet that panther. I felt like an old mountain woman with a child writing Jessie’s Mountain during those two weeks in 2007.

In the book, young Ernestine’s encouraging mantra is, “I’m five years old and a big girl.” It’s so sweet and simple, yet also feels relevant to the “take-no-BS” female empowerment of 2019. Was this intentional? How did this line come to be?

When Lucy was four-years-old, she was tight-rope walking on a tall curb. I said to her, “Be careful, Lucy,” and she to me, “Hey Mama! Am I two or am I four? I am a big girl, Mama!” And I never forgot — she was so sassy and didn’t suffer fools. A lot like the real Ernestine! Growing up I ate up books, movies, and musicals with strong girls — Caddie Woodlawn, Francie Nolan, Laura Ingalls, Frankie Addams, Mary Lennox, Katie John, Jane Eyre, Pippi Longstocking, Sara Crewe, the Unsinkable Molly Brown, Princess Leia, Dorothy Gale, and so many others. I loved stories of girls who were not girly-girl. Football so dominated my life that I longed for stories to show me how to live a life apart from the gridiron. I didn’t belong in that world of cheerleaders and coaches’ wives, and I wasn’t allowed in the locker room either, so my life was “offsides.” But I have to say the seed was planted when little Lucy pointed her finger at me and said, “Hey am I two or am I four? I’m a big girl, Mama!”

Ernestine’s Milky Way is available now for pre-order. Available March 5th, 2019!