Meet Noa Jones, Author of How Do You Know What You Know?

Interviewed by Liza Frenette

Note from Susan

For the past eight years, I’ve shared profiles of inspiring colleagues and friends, and this month’s spotlight on Noa Jones is no exception. Noa is the executive director of Middle Way Education, where she combines creative work with leadership in Buddhist education. She collaborates with Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche’s sangha and other communities worldwide, helping to create learning environments and share wisdom-based curricula.

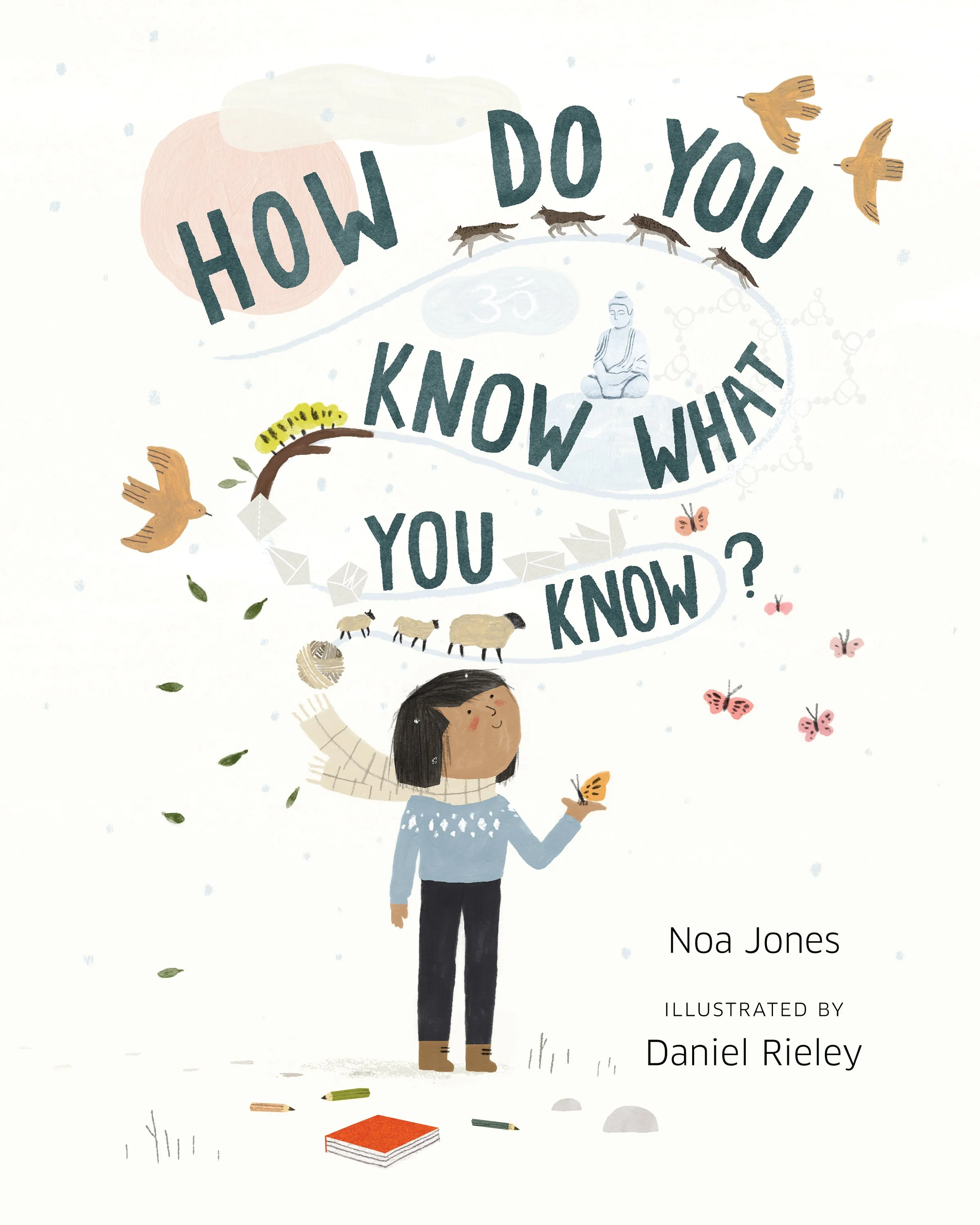

I want to highlight Noa’s work now because she’s just published a beautifully illustrated children’s book called How Do You Know What You Know? Inspired by her work at the Middle Way School in upstate New York, the book encourages kids (and adults!) to ask questions and explore how we form opinions.

Noa’s book reminds us all of the importance of curiosity, inquiry, and wisdom. Be sure to check it out!

What was your inspiration for this beautiful, thought-provoking picture book?

The inspiration came from a moment at the Middle Way School, where I used to teach. It was lunchtime, and one of the students suddenly said, "This politician is the worst!" I was struck by the certainty in this five-year-old's voice. I thought, how does this young child already have such strong opinions? It made me reflect on how we're seeing so much division in the country, with people forming opinions shaped by forces they might not fully understand. We often don't stop to examine the information we're receiving. So, I asked the student, "Did you meet him? Have you ever heard him speak? Remember, he was someone's child, too. He has some good qualities, and someone must love him. Maybe before saying something so strong, it's important to examine if it's true."

The Buddha never said, "Here's the truth." He never claimed there was only one way.

As a dharma advisor at the school, I used to encourage teachers to reflect on who taught them what they know. It could be something as simple as learning to jump rope from a cousin. It's all about asking, "How does this person know that?"

With the rise of AI, people search for something and are bombarded with ads that reinforce specific ideas, often without showing them the other side of the story. This kind of selective exposure shapes opinions today.

Your author's note says it's important to know where our ideas and opinions come from so we are not swayed by hidden agendas. How is this relevant today?

Absolutely. The hidden agenda these days is often about profit. Companies are out to seduce us because the more clicks they get, the more money they make. But cultivating critical thinking and the habit of asking questions makes us less likely to be swayed by these influences.

How do you encourage students to develop the habit of inquiry?

One approach is having teachers identify their own teachers—people who taught them something valuable—and share that with the students. For example, if someone brings an owl into school for a nature study, students might ask, “How did you learn that about the owl?” or “What got you interested in owls?” For my book, you could ask students, “Where do you think it was printed?” or “What can you learn from the front cover?” They could even look up words they don’t know. We also give students tools to ask respectful questions of people who might have different views because you can’t get to know someone if you approach them aggressively.

How else do you support educators?

We have a librarian who consults for the school and works with Middle Way Education. She puts out stacks of books everywhere, and we drink tea while sorting them into piles. She'll lay out books for the teachers when we're focusing on a theme—like impermanence. They pick a few to take home and then present how those books connect to the theme to other teachers.

We have units on cause and effect and lineage. For instance, we explore the history of the school, the country's history, natural heritage, and what students want to contribute through their body, speech, and mind. It's all about encouraging teachers to trust their own understanding.

You speak of the importance of lineage—knowing where things like drinking water and our clothes come from.

Knowing where things like drinking water and our clothes come from leads to a sense of connection and accountability.

Do you take this further with students, asking them to take action if they discover lineage is questionable (e.g., clothes made by sweatshop labor, or the unfairness of a law)?

Yes. One teacher led a huge study on sweatshops and child labor; the students even organized a food drive. Using the principles of engaged Buddhism, we encourage students to take action—whether it’s deciding what they want to disrupt, continue, or adopt.

Middle Way Education’s lesson plans often use Buddhism's Four Noble Truths as a framework. We examine the problem, its cause, the solution, and the path to that solution. It could be as simple as figuring out how to protect chickens from being eaten by foxes, like building a higher fence or addressing a broader global issue. Kids love exploring the world through this lens. I tried not to teach morals; we teach logic. Our approach honors children's wisdom.

What is something you discovered in inquiry about your life, surroundings, or work that inspired you to make a change in your beliefs or lifestyle?

When I finally met my guru, who agreed to teach me the Dharma, he insisted that I ask questions and not take his words at face value. This approach felt natural because my father was the same way. He never accepted things without questioning. We would always read the fine print on fruit stickers to see where they came from, or when browsing yard sales; he could tell the difference between authentic pottery and something mass-produced. That kind of continuous investigation has constantly shaped my thinking. The act of questioning became a core practice for me. So when I met my Bhutanese lama, I naturally asked, “How did you get to be who you are? What’s your story?” This habit of inquiry continues to deepen as I explore my own biases.

In your book, the father says it is important to make time for things that make other people smile, even if they have no other purpose. Do you think of this book like that?

I definitely smiled when I saw the illustrations! I believe that personal practice is so important—and so is joy. It's the simple things, like making my altar look beautiful with fresh flowers, clean water, and nice bowls. Lighting a candle during the day may not serve a practical function, but it changes the atmosphere and makes me feel delighted. At our school, every child gets to light a candle on their birthday instead of blowing it out. We also encourage children to do delightful things, like playing tag.

As an educator, author, writer, and editor, you’ve written this book and also articles for the New York Times, LA Times, Tricycle, Lion’s Roar, Vice, and Buddhadharma. Do you focus on recurring themes or address different issues?

I write about the Dharma a lot, and I’ve edited books for Buddhist teachers. My style is about translating complex ideas into relatable concepts. When I wrote for the LA Times, I covered a wide range of topics—from a backgammon club at a Croatian center to a person who rents out doves for weddings. Now, I am writing more about Dharma, and it's interesting.