Meet Rev. Dr. Jacob Bolton on Lifelong Learning, Interfaith, and the Healing Power of Awe

Interviewed by Maisie Hurwitz

Earlier this year, Maisie spoke with Presbyterian minister Jacob Bolton to feature him in our shout-out profile series, which highlights the incredible work of friends and colleagues—and in this case, a family member! Maisie was fascinated by how Jacob came to his role as Associate Pastor for Christian Formation at Westminster Presbyterian Church in Washington, DC—a part of their conversation we’ll share in full in our next post.

But first, I wanted to offer a sneak peek into Jacob’s refreshingly openhearted approach to lifelong learning, contemplative practice, and meeting people where they are—including the inspiring wisdom he brings to his community.

I’m proud to call Jacob my nephew and to share his insights here, especially his thoughtful commitment to interfaith dialogue. (To see these values in action, take a look at this powerful resource he helped create on behalf of the U.S. Presbyterian Church to help congregations confront Christian nationalism and religious-based attacks of any kind.)

His conversation with Maisie is both grounded and expansive—offering a wider lens on faith and practice, along with thoughtful suggestions for how to stay awake to life’s ineffable moments and nurture a spirit of lifelong curiosity.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Across wisdom traditions, lifelong learning is a key element of living a fulfilled life. How can we keep ourselves open to curiosity and lifelong learning?

There are lots of different ways in. I'll start with a more uplifting way, which is something like awe. Where do you experience awe? That could be in nature, or with your pet, or even just encountering somebody that you were not expecting to encounter while on a night out with friends. There's this new telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope, where all of a sudden we can see way more into the universe than we ever could before. I mean, so many people are like, ‘holy cow, this is just so vast.’ The firmament is incalculable, but that doesn't necessarily make someone feel bad or inconsequential. It actually makes somebody feel awe—look what I'm a part of. How can I, in my role as a clergyperson, care for that? How can I continue to be a greater part of that?

Can you talk about other ways that people can experience the ineffable, the non-conceptual, the hard to put into words, and how you incorporate that into your work as a minister?

Experiencing art is one way to get into this ephemeral state of awe. There is only one Leonardo da Vinci painting in the Western hemisphere, and it’s here in Washington, D.C., at the National Gallery of Art. We have brought people from our congregation to that exhibit so that we could see the painting. That’s a very different experience—but just as striking, artistically—from walking a mile down the National Mall and seeing all of the shoes at the Holocaust Museum. What does a Leonardo da Vinci work carry, and what do those shoes carry? And—I can't even speak about this without being moved—where does that bring individuals? Where does that bring us? I believe it brings us to a very profound place.

I also think space is an important factor, and that’s part of why pilgrimage in so many traditions—be it monotheistic or polytheistic, Abrahamic or not—is so vital. In Catholicism, people walk the Camino de Santiago, which is a pilgrimage across Spain. The Hajj is one of the five pillars of Islam: go to Mecca once in your life. Malcolm X said that going to the Hajj and being in Mecca was the most powerful moment of his life because he saw people of all races doing the same thing together.

But it does not have to be across the world. Wherever one happens to be, there probably is a sacred glen or a brook or someplace where you can experience something deeper, something ephemeral.

What challenges do you encounter when you're introducing people to these contemplative or non-conceptual experiences that are hard to put into words?

For the newest folks to any of these practices, I think of it like meditation training wheels. Sometimes people set the expectation too high. But I say, if somebody's able to have five minutes of silence, let's count that as a win. I'm a reverend doctor, but I'm not going to sit here and tell you that I can do 45 minutes of mindfulness in silence and not have other things pop into my mind, right? To me, the amazing thing is that you showed up and you tried, and we're starting a journey together.

But mindfulness can look like many different things. When someone asks me a question, for instance, about a Biblical story, that's not mindfulness in the sense of somebody trying to center themselves or find calm in a moment. But it definitely does speak to how a text, or a story, or a sacred narrative can impact somebody's life about what is truth. The sacred is often sort of thought of as way out there, but how can we also note the sacred that is here and present, however we encounter it?

Can mindfulness and Christian spiritual practices complement one another? Do you use mindfulness techniques explicitly in your work at all?

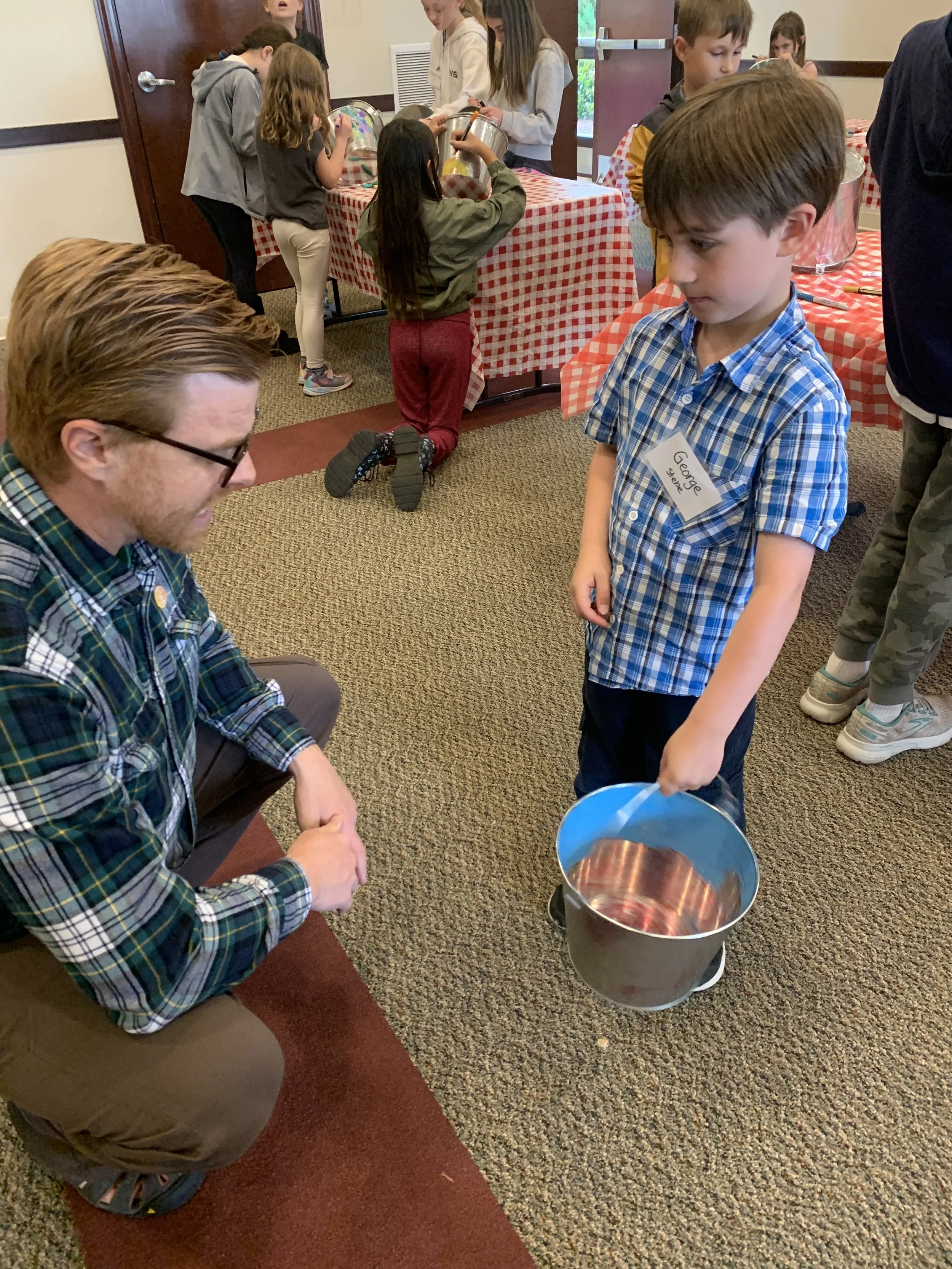

I find mindfulness and Christian spirituality to be able to coexist, a hundred percent. The mindfulness practice that I use the most—that is a Susan Kaiser Greenland gem—is from Mindful Games, and it's the Pass the Cup game. You have a cup of water, and you try to pass it around the circle without spilling it. And then you try to do that with your eyes closed. As a Presbyterian reform theologian, what I like most about that is that it’s both mindfulness and community. You are working with one another to do this task, and you do it silently. I love doing that with adults, with staff, on a retreat. It hits all the markers—it involves movement, it’s grounding, but it’s also contemplative.

What does interfaith mean to you, and why do you believe it’s important?

Interfaith is something that I’ve valued for a long time. I was raised Presbyterian, but I'm lucky I had Jewish friends growing up, and I went to a Catholic high school, which gave me a completely new experience. I had the opportunity to attend the biggest Presbyterian seminary, but I chose to go to Union Theological Seminary in New York City instead, where I could study at Jewish Theological Seminary and take classes at Columbia.

There was a saying in rural Michigan where I grew up that went: ‘the two biggest days of your life are when you're wed and when you're dead,’ meaning your marriage and your funeral. But I think there's a whole lot more than just those two days. My hope is that no matter the tradition, faith communities can be a part of the celebrations, the lament, and the continual formation of everyone who finds themselves home in one of them.

How do you work with those who have been harmed by a faith tradition to experience spirituality again in a way that is healing?

There are many ways we can bring people together to a deeper place that involves mindfulness and is restorative and healing. We have book clubs here where people read the same story and then gather around, and people say it's their favorite time of the month, just to sit together around the same story and reflect. For people who have been harmed by the church, or by any faith tradition—that could be as terrible as clergy abuse, to the church not acknowledging your second marriage, to refusing to give you a certain position of power—it’s important to acknowledge, first, that it’s not their fault. One of the things I try to do is liberate people from carrying guilt or shame so that they can move into a healthier position. That can involve prayer, time, counseling, or ritual. But the goal is to move into a more grounded, healthier space spiritually. And it looks different for each person, or each family unit, but it often starts with acknowledging that it wasn't their fault.

Can you leave us with some wisdom from your tradition that can offer hope in today’s world?

The Presbyterian Church has something called the Book of Confessions, which are statements made by communities throughout history about what they believe in that moment. Some of them were written in the year 395; some were written in the year 1650; some were written in the year 2021. They're all from different eras and different communities: some were written by churches that were being persecuted by the Nazis in 1939 in Germany; some were written in 1967 intentionally speaking about the power of women; some were written in apartheid South Africa, condemning it. Each has its own context, and each is clearly stating how that community is seeing God in that moment.

How do we apply the wisdom we learn from all those eras of writing to how we live our lives now? We're not living in 1967, we're not living in 395, but what they were thinking then can inform our thinking, our belief, and our practice now. Ideally, we can move forward together in a way that does more beneficial work for the world.

Climbing Trees

Jacob brings the same generous, expansive thinking evidenced in this profile to his conversations on Climbing Trees, a podcast he hosts for Westminister Presbyterian Church. I joined him for an episode that touches on many of the themes we’ve explored here—mindfulness, meaning, and the power of showing up. You can find Climbing Trees on Spotify, iTunes, or wherever you listen.